With all the world's troubles reaching occasional fever pitches, it's comforting to know that scientists continue to explore and expand our shared knowledge of the universe.

A case in point is the

Planck Telescope. This spacecraft was launched in 2009 by the European Space Agency (ESA) with the mission of "mapping the oldest light in the Universe," according to a recent BBC report. The British article noted that the telescope, which has delivered far more than anticipated, is reaching the end of its functional ability.

The details about the mission are remarkable. For the Planck Telescope to properly work, its instruments have had to operate in temperatures well below 250 degrees Centigrade. At its most extreme, the telescope functioned within one-tenth of a degree above absolute zero. I don't have any scientific background, but the telescope's ability to work in such extraordinary environments strikes me as just slightly south of the miraculous.

The telescope's mapping features are fascinating in their own right. I can't pretend to explain them, but the

BBC story discusses them in reasonably accessible terms for laypeople to grasp. One profound area of research Planck scientists contemplated and researched was a notion called "inflation." The concept, as the BBC article noted, is a "'faster-than-light' expansion that cosmologists believe the Universe experienced in its first, fleeting moments." It also touched on the idea of "ancient light," or elements that existed long before the Age of the Dinosaurs, or before anything we could possibly associate with our planet (including its own existence).

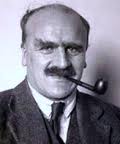

As the late British scientist

J.B.S. Haldane (shown in photo) famously said, "My own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose."

I'll second that motion.

No comments:

Post a Comment